Nicolai Schmidt

Nicolai Schmidt (II), born on September 29, 1839 in Steinbach, Molotschna as the son of Nicolai Schmidt (I) and Katharina Matthies; died on December 28, 1876, father of Nicolai Schmidt (III), the last temple chief in Jerusalem. Important personalities are connected with the name Nicolai Schmidt in the movement of the Württemberg Templer. A look at the origins of the family leads from Jerusalem back to the northern edge of the Caucasus Mountains, then a thousand miles further back to the Molotschna in today’s Ukraine, from there back to the Vistula River near Gdansk and finally back to the Palatinate and Switzerland. Heinrich Schmidt (I), a Mennonite, had emigrated from the canton of Bern to Alsace around 1730.

His son Daniel and his family ran a larger farm near Zweibrücken in the Palatinate. His son Peter was just 20 years old when Napoleon’s great conquest began and all the young inhabitants of the occupied territories were drafted into his army. As Mennonites, the Schmidts refused the service with the weapon and so, given the circumstances, they had no choice but to flee from the conqueror. One night in the year 1809, they hastily left their farm and all their possessions. On foot they made their way to Galicia, where other Mennonites lived in the Lviv region. The following year they moved on to Russia, far to the south, to the river Molochna, which flows into the Sea of Azov near Melitopol. There Mennonites had already founded a few villages. The Russian Czarina Catherine II had invited German settlers to contribute to the development of this area, promising them free exercise of religion, preservation of native language, self-government, tax relief and exemption from military service. In the Gnadenfeld educational establishment of Peter Schmidt’s son Nicolai Schmidt (I), for the first time in the German colonies in southern Russia, the ideas of the “Jerusalemsfreunde” from Wuerttemberg found their feet. After several years this was followed by disagreements between the settlers, so that in 1863 covered by the temple thought some saw theirselves forced first to form their own community in Gnadenfeld and then later (1868) to move away from the Molotschna completely and to found an own colony in the Kaukasus foreland, “Tempelhof”. After the first temple colonies had come into being in Palestine, Nicolai Schmidt also thought of relocating there. In 1869 he visited Palestine and bought land in the Refaimebene, today’s Jerusalem district German Colony, with the aim to settle there. But on departure, he died unexpectedly on September 14, 1874 in Taganrog.

His son, Nicolai Schmidt (II) had already moved in 1872 from southern Russia to Jerusalem and began building a house. The laying of the foundation stone in 1873 for the house and mill in the “Emek Refaim” marked the beginning of a new Templar colony. A year later, his wife Anne gave birth to his first child, the daughter Rephaemie “Repha” Schmidt (1874). Nicolai tried to make a living by oil-pressing linseed and mustard. However, the Arab population did not win for it and preferred olive oil from the Arabian oil mills. Then first plantings of vines on the road to Bethlehem had success. Winemaking, production and distribution should become the professional goal of Nicolai. When his son Nicolai Schmidt (III) was born at the beginning of the year 1876, family happiness was combined with the professional success of the aspiring farmer. However, this luck was short-lived, because Nicolai Schmidt (II) died in December 1876 at just 37 years. He had to leave his wife Anna with two small children. Anna married three years after Nicolai Schmidt’s death in 1879 a Templar from near Stuttgart. Together they continued the wine business of Nicolai Schmidt. The Jerusalem wines were later exported to Germany and then traded especially in Stuttgart. His son Nicolai Schmidt (III) will be the last temple leader in Jerusalem (1941-1948) and with him the era of the Palestine communities will come to an end.

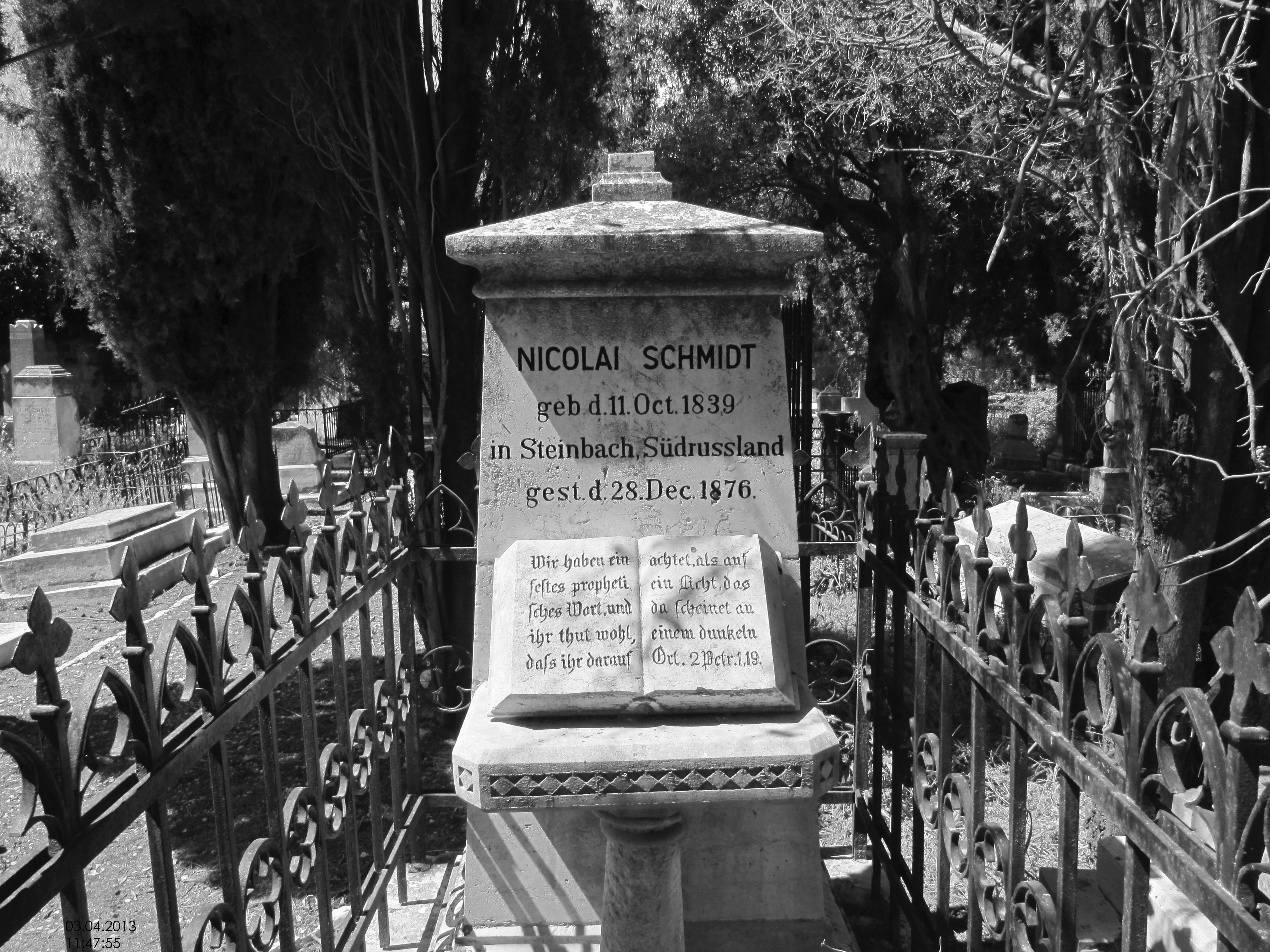

Nicolai Schmidt (II) was buried in 1876 in the Protestant Zion cemetery in Jerusalem. It took a strong sense of mission to take root in the heavy living conditions of Jerusalem in the late 19th century. This is attested to us in his gravestone inscription:

“We have a firm prophetic word,

and you do well that you pay attention

as a light,

that shines in a dark place.”

2 Petr 1,19.

The funeral of the earliest settled in the German colony settlers was still on the Zion cemetery, since the cemetery of the Templar colonists in Emek Refaim was created in 1878. Nicolai Schmidt (II) was the last of his family to be buried on the Prussian-Anglican Zion Cemetery.

After high school, Adalbert studied medicine in Vienna, and in 1872 became a Doctor of medicine. In that same year he graduated with a Master of Obstetrics. In 1874 he completed his training as a surgeon. After completing his military medical service, he committed to a two-year medical service with the Ottoman army in 1875, where he was stationed primarily in Nablus. However, this choice meant he had to give up Hungarian citizenship.

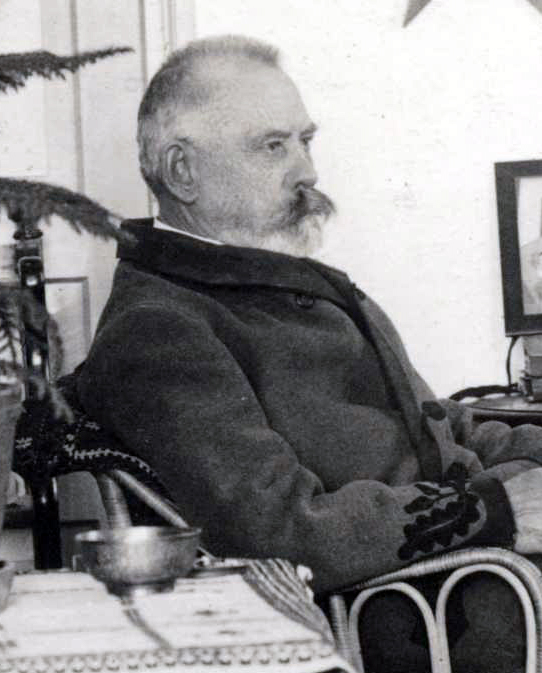

Dr. med. Adalbert Einsler

Dr. Adalbert Einsler was born on 24 May 1848 in Temesvar, which lay in the Hungarian part of the imperial and royal monarchy. Temesvar belongs to the Banat, which, like neighboring Transylvania, was populated mainly by German-speaking Danube Swabians. Today, the city belongs to Romania.

After high school, Adalbert studied medicine in Vienna, and in 1872 became a Doctor of medicine. In that same year he graduated with a Master of Obstetrics. In 1874 he completed his training as a surgeon. After completing his military medical service, he committed to a two-year medical service with the Ottoman army in 1875, where he was stationed primarily in Nablus. However, this choice meant he had to give up Hungarian citizenship.

After completing military service, Einsler worked for two years in the hospital in Tantur.

On May 15, 1879, he married Lydia Schick, the eldest daughter of the Württemberg government building officer Dr. h. c. Conrad Schick in Jerusalem. At that time, he converted from the Catholic to the Protestant church and assumed the Württemberg nationality.

From 1880 to 1884 he held the position of city doctor in Jerusalem, and was active in 1885 in Gaza, where he was employed as a microbiological expert in the control or containment of cholera medication. To emphasize the importance of this mission, one has to realize that there was no specific therapy for cholera at that time (neither vaccination nor antibiotics). In the same year he took over the medical management of the German-Israeli Biccur Cholim Hospital and the medical care of the leprosy asylum, “Jesus help”, of the Moravian Brethren. The sisters, who dedicated themselves to caring for the sick, came from Niesky.

The care of lepers was a special medical and scientific concern. He wrote a monograph “Observations on the leprosy in the Holy Land” (published in 1898, publishing house of the mission bookstore Herrnhut). At that time there was a great controversy as to whether the leprosy was of infectious or hereditary genesis. According to eyewitnesses (Otto Stahl, pastor in the Middle East and Swabia) he was of the opinion that it was impossible to decide the question of whether leprosy in Palestine was hereditary or contagious or both due to the data.

As is often the case with violent disputes, it turns out later that both sides are right. Leprosy is undoubtedly caused by Mycobacterium leprae, but less than 5% of people who have had contact with the pathogen also suffer from leprosy, which is mainly due to hygienic protective measures, but also to a genetic disposition. By the way, none of the sisters of asylum ever had leprosy.

In 1899, the German Emperor awarded him the Order of the Red Eagle, and in 1913 he was awarded the title of Medical Councilor by the King of Württemberg, and appointed by the Dutch Queen as Dutch Consul in Jerusalem.

Einsler died in Jerusalem in 1919 and was buried in Zion Cemetery.

Norbert Schwake honored his significant position in Jerusalem society and medical profession and highlighted it in several publications.

The Einsler family had 8 children, and sadly the family was not spared severe fatalities. The second-oldest son, Cony, was bitten by a rabid dog at the age of 9, and his father, a medical doctor, had to watch helplessly as his son died painfully from the disease. Today, it would be possible to cure the disease with a vaccine, but due to a lack of access to therapies, at least 60,000 people in Asia and Africa still die each year of animal-borne rabies. His son Friedrich, a lieutenant of reserve, was seriously injured in front of Reims in World War I and succumbed to his injuries in the hospital Rethel. He is remembered on a plaque in Zion Cemetery. All the other children except Walter, who remained in Jerusalem until his death, moved back to Germany, while the youngest daughter Gertrud married an American pastor (Tatley) and emigrated to the United States. There she wrote several articles about life in Jerusalem and the conventions and customs of the Arab population.

One may wonder why we should still be interested in the lives of our ancestors today. Although the individual stages of life are interesting enough, the attitudes and characteristics of the people at that time are particularly fascinating. At a time when today almost everyone strives for protection and self-optimization, the trust in God and the confidence of this generation are impressive. When emigrating or settling in Jerusalem, nobody had a pension, return ticket, or career guarantee, and yet people like Dr. Ing. h. c. Conrad Schick, Dr. Adalbert Einsler and his wife (to name but a few examples) accepted their duties with great confidence and trust in God. They believed in their mission even in difficult situations and made the best of the circumstances, but they also accepted the results without reservation. I think we could learn a lot from them today.